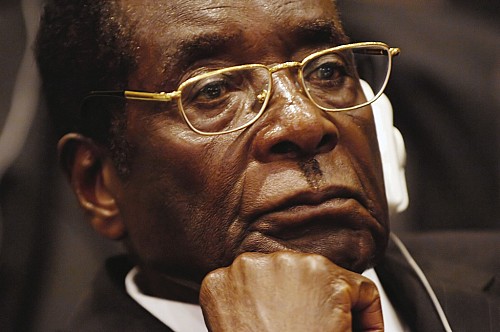

Inside Mugabe's Zimbabwe

As the tyrant totters towards decrepitude, his country slides into famine...

Zimbabwe's schizophrenia is in vivid evidence on Friday afternoons in the capital Harare's leafy northern suburbs. At the Tin Roof restaurant round the back of the Chisipite Shopping Centre, white, sun-baked former farmers gather for a lunch of barbecued ribs and cold Castle lagers, and to talk about the good old days. The owner, Leith Bray, was run off his Tengwe farm in 2002 by a baying mob intent on killing him, but he now laughs that off as part of life's rich tapestry and gets on with his new career as a restaurant proprietor. "That's what Zimbabweans do – they make a plan," says Bray.

Half a mile away along Enterprise Road, past the desperate, ragged street-corner vendors selling everything from mobile phone airtime for nickel-and-dime commissions to rhinos and elephants made from beer cans, a more contemporary crowd is dining on fusion cuisine and South African chardonnays in four acres of lush, beautifully landscaped gardens. Amanzi Restaurant is owned by Andrew and Julia Mama, a gregarious Nigerian-British couple who fled sectarian violence in Nigeria to settle in what they regard as a relatively peaceful African country. Amanzi draws in the diplomats, NGOs, aid workers and visiting European doctors, all of whom give the Zimbabwean capital a veneer of prosperity and normality.

But right now Zimbabwe is anything but prosperous and normal. Robert Mugabe and his ZANU PF government, while greatly enriching themselves, have run this country into the ground. It is bankrupt and this year faces a famine of epic proportions – there is a shortfall of more than a million tonnes of maize and, at the time of writing, Mugabe's government has failed to issue a letter of appeal to the United Nations, standard procedure to get the World Food Programme activated. According to opposition member of parliament Eddie Cross this is either down to Mugabe's "pride or simply lack of attention". On such whims, it seems, hangs the fate of millions of Zimbabweans.

At the same time the economic sectors – manufacturing, mining and agriculture – that were once the engine room of a productive and innovative small economy are grinding slowly to a halt. The second city Bulawayo, once the hub of the nation's industrial output, lies still and silent, the Detroit of the Zimbabwean lowveldt. At independence, manufacturing contributed 27% of the country's GDP and employed more than one and a half million people. Last year more than 100 businesses in Bulawayo closed their doors and, of those surviving, 60% have been placed under judicial management. Those who are still there are just hanging on. Making a plan.

The blame for this economic torpor lies unequivocally with Mugabe and his ZANU PF. These days the 91-year-old is known in Zimbabwe as "a visiting president", as in a visiting college professor. His role as President of the African Union – another bankrupt African organisation that depends for survival on largesse from the West – has him jetting from one AU constituency to another just as his own country appears to be locked in a death struggle. For the first time in 35 years of totalitarian rule Mugabe's political party is starting to tear itself apart, purging itself of former stalwarts, breaking into warring factions as the leadership contenders position themselves for the moment the Old Man dies.

The whole country is waiting for that moment. I have just spent a month travelling around Zimbabwe and, from the wilderness areas, through the rural communities, and in the major cities, the phrase that prefaces almost every conversation is "When the Old Man goes..." It will be a defining moment for the new Zimbabwe. But right now the Old Zimbabwe is clinging on by its fingertips. It is a situation that alarms David Coltart, a former Cabinet minister in the now defunct Government of National Unity (GNU). He says that since independence from white minority rule in 1980 "we have never had a situation where you've got weapons under the control of so many different entities – ZANU is fragmented, the army is fragmented, the Central Intelligence Organisation (CIO) is fragmented, the police are fragmented – and there is a leadership vacuum. As a country, as a people, we are at our lowest ebb."

The major contenders are, for the moment, 60-year-old Joice Mujuru, former vice president and widow of the assassinated former General Solomon Mujuru, and 69-year-old Emmerson Mnangagwa, vice president, hard man and living embodiment of ZANU PF's Stalinist Old Guard. Majuru was expelled from the party at its national congress last year, with Mugabe's wife Grace accusing Majuru of planning a coup, and she retreated to the farm bequeathed to her by the assassinated Solomon. From there she is apparently planning the first post-Mugabe government while she lives in fear of death. The MDC (Movement for Democratic Change) MP Eddie Cross says she is in great danger "and our advice to her has been for her to stay in ZANU PF and stay quiet. That may save her life."

Mugabe's government has in the past shown little mercy to its enemies. While Zimbabwe has all the outward appearances of a Western democracy – elections every five years, an outspoken free press ranging from State-sponsored ZANU PF publicity papers to independent anti-Mugabe dailies, and a carefully selected judiciary going through the motions of applied justice – underneath is a cruel and ruthless Stalinist state that treats every threat to the regime's rule with pitiless efficiency. Most recently, in early March, journalist and human rights activist Itai Dzamara was bundled into an unmarked car and has not been seen since. It is assumed he is dead.

Former ZANU PF chairman of the mines committee Edward Chindori-Chininga, after making a statement on corruption associated with the Marange alluvial diamond fields, was killed on a drive along a remote country road. The official version is that this was a road accident, but opposition politicians insist he was shot in the head while he was driving. Chindori-Chininga was buried within 24 hours of his death and there was no autopsy. MDC MP Eddie Cross remembers congratulating Chindori-Chininga on a brave parliamentary speech "and he said 'they're going to come after me'. Ten days later he was dead."

Even former darlings of the party have met with sudden termination when seen as crossing the leadership. Solomon Mujuru was one of Mugabe's trusted generals and closest allies during the liberation war, but in 2011 he was despatched with brutal force. It appears he'd arrived at his farm, was ordered out of his car and shot, and his body was taken into his bedroom whereupon it was set alight with phosphorus grenades. The building was also set alight.

At the subsequent inquest witnesses confirmed they had heard shots some hours before the fire and that Mujuru had been burned beyond recognition. The verdict, however, declared there was no evidence of foul play and denied the family's request for exhumation.

Several reasons are offered for Chindori-Chininga's and Mujuru's sudden deaths. Both had been critical for some time of Mugabe's leadership and both believed the time had come for change at the top. Also, both had criticised Mugabe's involvement in the Marange alluvial diamond operation that had made a small group of individuals seriously wealthy but had all but eluded contributing to the national treasury.

Between 2008 and 2013 the Marange fields in the country's eastern highlands, at the time the largest diamond-producing project in the world, yielded an estimated 120 million carats of diamonds valued at more than $12bn. Marange diamonds accounted for 10% of the world's supply and its reserves, estimated at 200 million carats, were the largest anywhere outside Russia. Today, nobody is certain about the precise value of Marange diamonds as very little was officially recorded and almost no revenue found its way to the treasury. Quite clearly a parallel economy was operating here.

That parallel economy has been feeding vast sums of money into ZANU PF coffers. In 2013 the American investigative platform 100 Reporters published Zimbabwean Central Intelligence (CIO) documents that revealed how $1bn in diamond revenues was invested in security and intelligence measures designed to rig that year's general election. Also, according to court papers filed by opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai, ZANU PF paid Israeli company Nikuv International Projects at least $10m to help manipulate the election.

Among the steps listed by the CIO were: "registering less than 10 real voters on any given day with direct command from Nikuv and the Party; populating the voters roll both before and during the elections to counter unfavourable voting outcomes; parallel registration and statistical manoeuvring, depopulation and population of hostile constituencies," in co-ordination with the Registrar's Office and an official of the Chinese Communist Party identified in the documents as Chung Huwao. A list of other nefarious activities were laid out, all "as advised by Nikuv".

Seven major companies, including Mbada Diamond Company, Anjin and China Sonangol, operate the Marange diamond fields and all are connected to the Zimbabwe military and ZANU PF politicians. Mbada for example is headed by Robert Mhlanga, Mugabe's former pilot and widely known to be a close business associate of the president. (Mhlanga was also prosecution witness in the bizarre 2003 treason trial of MDC opposition leader Morgan Tsvangirai.)

Anjin, on the surface a joint venture between an obscure Zimbabwean firm called Matt Bronze and a Chinese construction company, is in fact a joint venture between the Zimbabwean generals and Chinese party officials; and China Sonangol, via a labyrinth of holding companies, is connected to the Queensway Group, whose principal owner is Sam Pa, currently under sanctions from the US Treasury for actively supporting Mugabe's regime. According to a report by the British anti-corruption watchdog Global Witness, based on documents leaked from Zimbabwe's CIO, Pa's company had been allowed a share in the diamond fields after he donated 200 vehicles and $100m to Mugabe's secret police.

Today it seems the Marange fields have been picked clean and are all but empty of alluvial diamonds, with the bulk of the money having gone abroad. Which partly explains why the government can no longer pay its Civil Service on time and has failed consistently to pay its debts here and internationally. The amount of that vast revenue that made it to the Treasury in taxes is tiny. Eddie Cross says he "doubts that more than $200m in total came in".

Environmental catastrophe

As the sun-baked farmers at the Tin Roof restaurant will tell you, the biggest calamity over the past 15 years has been the collapse of commercial farming. Before Mugabe turned his militant gangs, whom he passed off as liberation war veterans hungry for land, on the white farming community early in 2000, agriculture was the bedrock of the Zimbabwean economy. At that time there were 5,000 white farmers, the country produced more than two million tons of maize – a surplus of 300,000 tons – and more than 240 million kilos of high-grade tobacco. There were also prosperous dairy and beef industries that satisfied local demand and earned precious foreign exchange. Zimbabwe was indeed the breadbasket of southern Africa.

Today there are fewer than 350 white farmers left working the land and, although some legitimate black farmers have replaced the whites, many of the most productive farms have been handed to ZANU PF politicians and cronies – pliable judges, retired generals, provincial administrators, girlfriends of ministers – who have become known as weekend farmers. Hendrik Olivier, director of the Commercial Farmers Union, says the so-called land reform programme has been a disaster. "The government touts the tobacco industry as a huge success but it isn't," he says. "In 2000 there were 2,000 commercial farmers producing more than 240 million kilos of tobacco. Today we have 100,000 people registered as tobacco farmers and we're producing less than 160 million kilos of poor quality crop. That is not a success."

These small farmers are also in the process of creating an environmental catastrophe. Last year 350,000 hectares of indigenous timber, mainly msasa forests, were cut down, much of it to flue-cure tobacco. The farmers do not have the infrastructure, financial resources or means of transport to transfer the necessary coal from the Hwange collieries in the west of the country as their predecessors did, so they have taken to the most accessible form of fuel in the area – the msasa forests. So serious is the problem that foreign diplomatic missions have confronted the government over the issue and one diplomat told me "we are hoping they (the government) have the sense to realise this has to stop. It is terrible. It is people going for the short-term solutions."

According to Ben Freeth, one of the best known of the evicted white farmers, the destruction of the old farming system has led to the displacement of more than two million black farm workers and their families. He says that even the working commercial farms today employ very small numbers by comparison, leaving a large unemployed rural community struggling to survive. He points out that former Zimbabwean farmers who have been accepted with open arms by the Zambian government have helped turn that country's agricultural economy around. It is the Zimbabweans' innovations that have transformed small-scale growers in their adopted country into productive farmers, upping their production from half a ton per hectare to between four and five tons a hectare. This year Zambia will be the only southern African country with a maize surplus and, ironically, will be exporting 300,000 tons of wheat to its starving neighbour, Zimbabwe.

Freeth and his father-in-law Mike Campbell were run off their Mount Carmel fruit farm by Peter Chamada, the son of Mugabe's close political ally Nathan Shamuyarira. They and Freeth's mother-in-law were abducted, tortured and beaten by a gang of Chamada's storm troopers. The family took their case to the African Union human rights court in Namibia and, although Mike Campbell was too severely battered to attend the final hearing, Freeth appeared, albeit in a wheelchair with his head swathed in bandages, to hear the court declare attempts to invade the farm illegal. Mugabe ignored the ruling and two months later the farmhouse was burned to the ground. Freeth and his family were finally driven off their farm. Mike Campbell, who said his torturers had turned him into an old man overnight, died two years later of complications from the assaults.

In June Ben Freeth, who continues to campaign for Zimbabwe's white farmers as executive director of the Mike Campbell Foundation, appeared before the US Congress's Home Committee on Foreign Affairs and claimed that although the white population on commercial farms had been cut to 5% of what it was, "ethnic cleansing of those rural areas continues. Those remaining farmers are persistently terrorised or criminalised and face two years in jail for committing the 'crime' of farming their land and living in their own homes on these farms – in a country that is starving."

When I ask him why he keeps campaigning Freeth says that his aim is to go back to farming "and black Zimbabweans say to us all the time 'don't leave, please stay'. That's what gives us hope and drives us. The people want us."

President in waiting

The vast majority of Zimbabweans I speak to want a new president, and a new government, as soon as possible. They dread the idea of another rigged election in 2018 that, given past form, may even fiddle a 95-year-old Robert Mugabe into yet another presidential tenure.

One name keeps coming up – Simba Makoni. An English-educated former ZANU PF minister, he became disillusioned with the party in the mid 2000s and resigned in 2008 to run against Mugabe and Morgan Tsvangirai in the presidential election. Though the precise numbers are disputed, he came a distant third – Tsvangirai won with around 51%, Mugabe recorded 40% and Makoni, with none of his rivals' financial or organisational backing, came in with 9%. Although he remains on the political margins, for many he is the people's president in waiting.

I meet Makoni at his Galleria KwaMurongo, an art centre and restaurant in Harare. He is in a rush as he needs to drive 250 kilometres to Mutare to back his Dawn Party candidate in the next week's by-election. Makoni has no illusions of victory as "we expect ZANU PF will have rigged it".

Makoni has supported the MDC's Morgan Tsvangirai in the past and recognises the need to form what he calls a "grand coalition" to oust Mugabe and his party. Makoni has travelled a long political road. He was educated at Leeds University during the 1970s Rhodesian War and returned to take his place in ZANU PF in the early days of independence. Then, he says, Mugabe and a small circle of insiders began to betray the ethical base of the liberation struggle. "Today the rulers are so far away from the visions, ideals, principles, ambitions of the liberation movement I was proud to be part of." He left ZANU PF in 2008 "and the day I announced I was leaving somebody in the party promised me I would be buried within a week". Seven years later he is still around, a principled thorn in his old party's side, a man several foreign diplomats describe as "the most ethical politician in the country".

The problem is the Zimbabwean political machine has little time for democratic issues or such subtle nuances as the will of the people. The machine is controlled by ZANU PF, and for the moment ZANU PF is controlled by Mugabe. However, Makoni says that old age is fast prising open the old dictator's grip: "Even physically, he can only sit up alert in his chair for 40 minutes. He's not there mentally or physically the rest of the time. "People ask me about Mugabe and I say he was genuine up to a point, then he changed, and I can tell in both time and mind when that change took place and to some extent why."

He says that in the late 1980s Mugabe lost three colleagues – Maurice Nyagumbo, who committed suicide by drinking rat poison, Enos Nkala, one of the founders of ZANU who accused Mugabe of assassinating rivals, and Edgar Tekere, who denounced Mugabe and constantly criticised ZANU PF corruption, so was expelled from the party in 1988. "They were the only people more than equal with Mugabe, the only ones who could say no, because it was they who brought him into the nationalist movement."

Today the voice in Mugabe's ear, according to Makoni and others, is that of his wife Grace. Her rise to prominence over the past 12 months has been spectacular even by Zimbabwe's warped standards of dynastic entitlement. Grace was a typist in the President's office when she and Mugabe began an affair, apparently sanctioned by his dying first wife Sally. Now approaching 50, more than 40 years the President's junior, Grace has been transformed from First Lady and mother of two children with Mugabe to leader of ZANU PF's Woman's League, thus landing a place in the ruling party's politburo. Along the way in 2014 she was awarded a questionable sociology PhD by the University of Zimbabwe, having enrolled on the course only two months earlier, and there have since been calls from Zimbabwean academics for her to give her doctorate back.

Makoni is sure the end of the Mugabe era is very close and "when he goes the door will open for us to rebuild and restore a modicum of esteem and decency and respect for ourselves." However he does fear a desperate attempt by the Mugabe dynasty to hang on to power and can't discount the widely despised Grace. "Grace wants to be there. It's unbelievable but it's true. She wants to be president. That's how irrational we have become."

'Drive the rubbish out'

Zimbabwe's economic desperation is there for everyone to see on the streets of the major cities. The roads are potholed, the lifts in most government buildings are either out of order or barely working, traffic lights at major intersections operate sporadically, there are constant power outages as the Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority (ZESA) struggles to keep up with demand.

The pavements of the capital are crowded with vendors selling every type of goods you can imagine, and now they have spilled out onto the cities' streets in numbers that grow every week. These are not poor uneducated people from the rural areas – these are former teachers, office administrators, car mechanics, skilled factory workers, all victims of a collapsed formal economy, all claiming this is the only way they can pay for their children's education and put food on the family table.

The African Development Bank estimates that at least two-thirds of working Zimbabweans are now engaged in the informal economy. (Out of a population of 13 million there are only 600,000 in formal employment, of whom 250,000 are civil servants.)

Now the Mugabe government has threatened to use military force to drive these vendors from the streets in what many observers see as a repeat of the army's attack 10 years ago on the country's squatter settlements, known as Operation Murambatsvina (a Shona word that means "drive the rubbish out"). Murambatsvina forced up to a million people from their urban slum dwellings across the country and attracted ferocious international condemnation, with a UN report calling it "disastrous and inhumane, representing a clear violation of international law".

As has been the case over the past 35 years Mugabe and his ZANU PF inner circle merely ignored the opprobrium and went about their business as usual. The real motive behind Murambatsvina was to clear Harare of large communities of dissatisfied citizens who had voted for the opposition MDC in recent elections – and in that light it was a great success. The voice of the urban poor was temporarily silenced. Today, however, the vendors provide a more complex problem as they are organised, articulate and economically desperate, and there is no reason to believe that Zimbabwe's spiralling unemployment will correct itself in the foreseeable future.

At the 2013 election Mugabe's key campaign pledge was to create two million new jobs but, given the economic circumstances, he may just as well have promised to create 20 million. As the International Crisis Group reported late last year, "Zimbabwe is an insolvent and failing state, its politics zero sum, its institutions hollowing out ... without major political and economic reforms the country could slide into being a failed state". The report concluded that "a major change is needed among political elites".

Take a short car journey from Harare's chaotic city centre, into the northern suburbs and beyond, and you will see the opulent lives being lived by those "political elites". Many of ZANU PF's major beneficiaries live in Borrowdale Brooke, the country's most exclusive suburb. The Mugabe family have their "blue roof mansion" there, a lavish 25-bedroom house surrounded by high walls and heavily armed guards, and one of Zimbabwe's richest and most controversial figures, Philip Chiyangwa, is also there. He is Mugabe's cousin and has a mansion with 15 carports to accommodate his extraordinary collection of luxury vehicles, plus 18 bedrooms, 25 lounges, two swimming pools and three heliports. And recently the former Reserve Bank governor, Gideon Gono, another ZANU PF insider, gave his daughter an extremely expensive house in Borrowdale Brooke as a wedding present.

Further north along Enterprise Road is another suburb, Gletwin, where the ruling elite has also been pouring money into ostentatious property development. Here three-storey mansions one would expect to see in Beverly Hills are under construction, the most recently completed being owned by the Chief of Police, Augustine Chihuri. Such visible examples of wealth amid the grinding poverty most of the country is enduring are shocking even to old Africa hands. One long-term Western diplomat now based in Harare told me that nowhere else on the continent had he seen wealth flaunted with such impunity and "nowhere else have I seen such segregation between the privileged and the poor".

Sanctions as smokescreen

Robert Mugabe blames white colonials generally for his country's current plight, and US and EU "sanctions" specifically for the parlous state of Zimbabwe's economy. While the invasion from Europe during the Victorian era may have destabilised a rural, tribal people and indeed exploited them in the 20th century, most of today's black Zimbabweans are so-called "born frees", born after independence and thus having no experience of colonial exploitation. They do not share their president's views.

The cover of sanctions is also tenuous, to say the least. The US implemented sanctions targeted against Zimbabwean government officials, security chiefs and state-owned companies in 2002 and extended these measures earlier this year because, according to President Obama, "President Mugabe and his associates continue to undermine Zimbabwe's democratic process". However, the US has continued to export goods to Zimbabwe and Zimbabwe exports goods to the US. There is no trade embargo. Equally the US continues to provide aid to the country – more than $2bn since independence in 1980.

So too the EU, which until last year applied what it called "restrictive measures" against 86 targeted individuals. The EU has now suspended its restrictions on all but two individuals – Robert and Grace Mugabe – which means the other ZANU PF officials can now travel in the EU and have access to their various bank accounts. So a constant stream of money, in the form of project-targeted funding to help prop up the education system, sectors of the health service, and agriculture, continues to flow in from Mugabe's historical enemies, the US and the EU.

However, the issue of sanctions has provided Mugabe with a convenient smokescreen for more than a decade. Zimbabwean economist John Robertson says that "the whole issue of sanctions was the most generous gift the West could have given Mugabe because he's played it out as the entire reason for the failure of the economy after the so-called land reform programme. In fact the US and the EU have fed this country throughout the bad years."

For all that, Robert Mugabe, as head of the African Union and chairman of SADC (Southern African Development Community) for the past year, has chosen to take an even more vituperative stance, stridently anti-West, anti-colonial and anti-white. Addressing the recent wave of xenophobia in South Africa, much of it directed at Zimbabwean migrants, he counselled Africans to direct their wrath against whites. "It's a xenophobia of whites not blacks, " he said. "They will say this Mugabe talks poison. I give poison not for you to swallow but to give to someone else."

Last year he vowed that whites, even Zimbabwean-born whites, would never be allowed to own land in this country again. At his lavish 91st birthday party in Victoria Falls at the end of the year he promised to clear the last remaining white farmers off the land and, noting that most of the country's safari industry is run by white Zimbabweans, threatened "to invade those forests" in the way they have invaded the farms. That last remark sent a shudder through the tourism industry, one of the few commercial sectors that remains relatively buoyant.

Despite this drip-feed of provocation and the constant anti-European rhetoric the people of Zimbabwe remain remarkably free of bigotry. Young white Zimbabweans have grown up without the colour prejudices that tainted their colonial forefathers while young, equally well-educated, black Zimbabweans who have travelled and worked in the West share none of this antipathy with Mugabe and the ZANU PF Old Guard. And even the older citizens who lived through the upheavals that came with transition from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe show a good will and forbearance that observers say will outlast the Mugabe regime.

Simba Makoni says he has mixed feelings about Zimbabweans' gentle forgiving nature "as it has been part of our undoing. That we can tolerate so much abuse makes it tempting to characterise us as cowards but then so much of what we have done in the face of this cruel, brutal regime has been extremely brave. "One thing is certain. Mugabe has abused us." Like everyone else here Makoni is waiting for the old man to die.