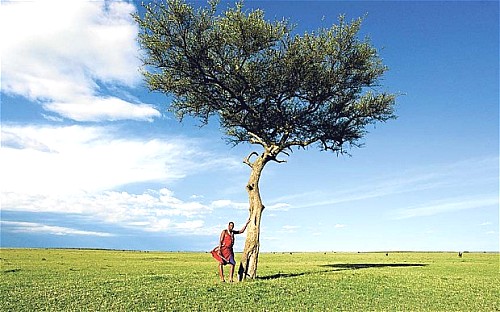

Kenya: the Maasai Mara faces a fight for survival'

Terrorist attacks in Kenya are having a crippling effect on tourist numbers, which could lead to the loss of 200,000 acres of a vital ecosystem, writes Graham Boynton

Conservationists in Kenya fear that the stay-away by international tourists following the recent wave of terrorist attacks threatens to turn some of the country’s fabled wildlife reserves into farmlands. Under the gravest threat are conservancies adjacent to the greater Maasai Mara reserve and operators there describe the situation as “dire”.

I have just returned from a visit to the Maasai Mara, arguably Africa’s most famous wildlife habitat, as it heads for the peak safari season, and although the camps and lodges were reasonably busy, according to Gerard Beaton, Kenyan country manager of Asilia, the safari camp operator, there has been a 30 per cent drop in tourism since the series of bombings in the country’s coastal towns and the subsequent US State Department and UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) travel advisories.

The FCO advises against all but essential travel to the Kenyan coast and also to “low-income areas of Nairobi” while making it clear this warning does not include or affect transit through Nairobi airport. However, the US State Department announced last month it was evacuating some of its Nairobi embassy staff, warning that “the US government continues to receive information about potential terrorist threats aimed at the US, Western and Kenyan interests in Kenya.”

Much of this signature-species conservation is down to the Maasai community benefiting from wildlife tourism. Operators say that if you take tourists and tourism revenues out of the equation a massive increase in poaching is inevitable. Some are already experimenting with alternative revenue streams and in the Mara North conservancy the ecosystem’s first abattoir has just been built and plans to market Mara Conservancy Beef are well under way.

So, as the wildebeest migration gets under way Mara safari operators and lodge owners wait with trepidation. This past weekend there were two more terror attacks, one in Lamu and the other in Tana River county, leaving 30 people dead. Against this backdrop of ongoing al-Shabaab terrorism, these operators are trying to salvage their vulnerable industry.

Those I spoke to in the Mara this month are angry at what they regard as “knee-jerk” blanket warnings from Western governments when the terrorist activities have centred on Kenya’s coastal region. They point out that wildlife areas such as the Mara are hundreds of miles from terrorist activities. However, to allay the fears of some of their American and British clients, operators such as Great Plains are avoiding transfers between Jomo Kenyatta airport and the light aircraft hub Wilson Airport by putting on charter flights to the Mara directly out of Kenyatta.

Others such as Asilia are avoiding Nairobi completely and re-routing clients through neighbouring Tanzania.

At the same time security in Nairobi has been significantly stepped up and at hotels such as Hemingways vehicles are thoroughly searched before being allowed through the gates and at Jomo Kenyatta airport there are long queues at various security checkpoints, but all the travellers I spoke to said they felt reassured.

As Asilia’s Beaton says, the Maasai Mara, and the conservancies in particular, now face a fight for survival. If tourism collapses in the wake of this murderous campaign then the terrorists will have achieved one of their major goals. There is much at stake.

Calvin Cottar, who owns and runs Cottar’s 1920s Camp, is absolutely clear about the impact that a serious tourism downturn will have. “All eight conservancies around the greater Mara ecosystem,” he says, “have been built on the singular foundation of tourist revenues and if this revenue dries up, as it has recently, our Maasai landowners will have no choice but to cancel the existing wildlife conservancies and resort to converting their land to farming maize or wheat instead.”

All of which seemed a little alarmist considering that on my visit there the United Nations Environment Assembly, attended by Prince Albert of Monaco, was being held in Nairobi, an international marathon featuring athletes from all over the world was taking place in Lewa, and planeloads of travellers were coming and going through Jomo Kenyatta International Airport seemingly without a care. And in the Maasai Mara I felt as safe as I do on Hampstead Heath on a Sunday afternoon.

However, news of the ongoing terrorist attacks has reverberated around the world and forward bookings are looking grim. Many of the camps and lodges in the Mara are reporting a wave of cancellations and although the July-through-September peak season is still showing reasonable numbers, after that a severe drop-off is expected.

The conservancies under threat, which currently cover almost 200,000 acres, are adjacent to the main 370,000-acre Mara Reserve and not only form a significant buffer zone to farmlands and ever-growing rural communities but are seen as a role model of community conservation practices.

They began forming 10 years ago, the brainchild of several white Kenyans, among them Gerard Beaton’s father Ron and Jake Grieves-Cook, a former chairman of the Kenya Tourist Board. They managed to persuade Maasai landowners to set aside large sectors of their land for wildlife, agreeing not to live on that land and only graze their cattle there at restricted times. In exchange they would receive a guaranteed monthly rent, a fixed amount whatever the number of tourists.

As an example, the pride of Beaton’s portfolio is the 50,000-acre Naboisho conservancy which has just five camps (134 beds) and pays the local community a guaranteed $1 million (£584,000) a year. “We had a couple of good years after we started in 2006,” says Gerard Beaton, “but political unrest and this recent terrorist campaign have meant it’s all financially fragile.

“It’s a shame because we have exceptional wildlife inside the conservancies and we believe that this is a role model for Africa.”

The conservancies also provide tourists with a more natural wildlife experience. While in and around the main Mara Reserve there has been almost unchecked growth in tourist lodges and camps – from 4,000 beds in 2008 to around 7,000 beds today – the conservancy camps have only 500 beds in total, so one seldom sees other tourists on game drives. You can also do walking and fly-camping trips in the conservancies and take night drives, all of which are off limits in the main reserve.