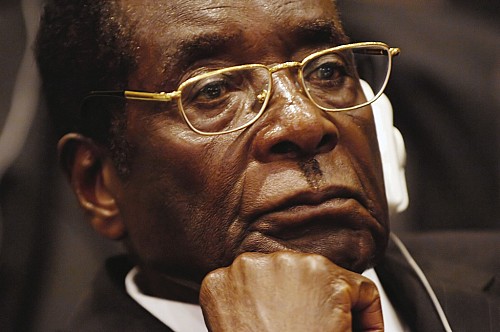

Mugabe's last throw of the dice

After 32 years in power, will Robert Mugabe try to fix one last election or stand down and give his party a five-year lifeline?

After three years of seemingly fruitless talks about a new constitution that would loosen Robert Mugabe’s 32-year grip on power, Zimbabwe is reaching a decision point.

Despite the pressure being applied by the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), led by South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma, to adhere to an internationally agreed process of democratisation, Zimbabwe’s political leaders appear to be preparing to abandon constitutional talks and hold a snap election in September or October.

Zimbabweans are bracing themselves for the announcement of an election, to be followed by a campaign of violence and another rigged result that will entrench Mugabe’s rule over this beleaguered, bankrupt country for a further five years.

Insiders say the military are in charge, and there are reports that the dreaded youth militia, who answer directly to Mugabe’s Zanu PF party, have already been deployed in the countryside to intimidate the population into voting for Mugabe.

This follows a pattern established in previous elections where Zanu PF operatives have beaten, tortured and murdered perceived opponents of the regime, mainly supporters of the opposition Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) party. People told me that they were seeing faces in the rural areas they hadn’t seen since the 2008 election.

I have just returned from a two-week tour of the country where I grew up and last visited during the 2008 elections. On that trip I watched Mugabe’s political machine turn defeat at the polls into victory under the noses of international observers.

Now, four years on, the country is limping, unproductive, unkempt and unsustainable, while the clique who rule have found untold riches in the recently discovered diamond fields in the east of the country.

According to several farmers I met, Zimbabwe is still unable to feed itself and they are predicting an even more serious food crisis this year. The gigantic grain silos that I passed on my drive from Kariba to the capital Harare were once beacons of the most productive farming country in Africa. Now they stand empty.

This year Zimbabwe will depend on food aid and the import of a million tonnes of maize from Zambia. The cruel irony here is that the Zambian maize is being produced by displaced white Zimbabwean farmers who have been welcomed by a Zambian government that, a decade ago, was importing that maize from the very same farmers in Zimbabwe.

Evidence of a country running on empty is everywhere. In Bulawayo, the second city and an MDC stronghold, the streets are so pot-holed that drivers are nervous of driving at night lest their headlights miss a crater and they rip their wheels off. The electricity supply is erratic with long daily power cuts the norm.

And the country has neither a national currency – it now trades in the US dollar – nor a national airline. Air Zimbabwe ceased operating a proper schedule in February. It cannot fly abroad as its aircraft would be impounded for unpaid fuel and airport charges. Although it does fly occasionally between Harare and the Victoria Falls, the planes are all but empty.

Meanwhile, the political partnership forced on Mugabe by SADC after the last election has been largely unproductive. Morgan Tsvangirai, former opposition leader turned prime minister to Mugabe’s president, has described the coalition government as ‘a mule – stubborn, sterile and stupid’. What it has given the country is three years of relative stability while the two parties wrangle over a new, more democratic constitution, a new voting roll, a referendum and then free elections, all due to be delivered by March 2013.

It is this very process that Mugabe, his generals and Zanu PF hardliners are threatening to scupper. One insider told me that in a properly monitored election Zanu PF would be ‘swept away and would thereafter cease to exist’.

These generals and political hardliners have calculated that the outside world is too pre-occupied with the global recession to be bothered about human rights abuses in far-away Zimbabwe, and having got away with widespread ballot-fixing (the Zimbabwe voters roll contains 3 million deceased citizens, all of whom doubtless vote for Mugabe) and campaigns of intimidation in previous elections they feel they may just about get away with this one.

It is a risky strategy as South Africa has threatened sanctions if Zimbabwe doesn’t follow the agreed course of a new constitution, referendum and internationally monitored elections. Some inside the MDC – including Tsvangirai – believe that Mugabe cannot pursue this course because the South Africans have made direct threats to close the borders and shut the country down. Zimbabwe has a seven-day stock of fuel, 14-day stock of food and 40 per cent of its electricity is supplied by neighbours, mainly South Africa.

This would be a high stakes gamble, but one can never underestimate Mugabe.

At the forefront of everyone’s minds is the issue of Mugabe’s health. He is reported widely to be suffering from prostate cancer and has been seeing doctors in Singapore on a monthly basis for the past year. A combination of the treatment he receives and his advancing years means he regularly falls asleep in cabinet meetings.

But just as rumours spread that he was on his deathbed in Singapore in April, he appeared at Zimbabwe’s Independence Day celebrations looking in good health and walked around the stadium for 30 minutes unaided, reviewing a military parade.

Mugabe’s health presents a dilemma for his supporters. If he dies in office, his vice-president, Joice Majuru, will step in for 90 days and then face an election which Tsvangirai appears bound to win and by such a majority that it would be impossible to fake a credible Majuru victory.

At a stroke, this would spell the end of the Zanu PF rulers and their grip on diamond revenues. This scenario has convinced some in Zimbabwe that Mugabe will proceed on the path of a new constitution, a distasteful option but one that would give the current leadership a five-year breathing space.

According to Eddie Cross, the MDC’s policy co-ordinator, Mugabe has no option but to follow the programme of democratisation. He believes that a deal is being done behind closed doors between Mugabe and Tsvangirai that will pave the way to Mugabe stepping down at the Zanu PF congress at the end of the year, and Tsvangirai running for president against Mugabe’s anointed successor, probably Majuru, next March. The deal will stipulate that, whoever wins, the current coalition government would continue to operate for another five years.

The tensions over Mugabe’s future are already apparent in a power struggle inside Zanu PF. Vice-President Majuru appears to be the strongest candidate to succeed Mugabe, but being seen as the (almost) acceptable face of the party by the MDC has made her an enemy of the hardliners. Emmerson Mnangagwa, the Defence Minister and a Mugabe confidant, announced in May that he was ‘ready to rule’ if chosen.

Will Mugabe bow out at the end of the year to give his cronies five more years of power? Or will he cling on to his last breath, believing that the Zimbabwe he created would collapse without him?

At his recent 88th birthday celebration, Mugabe declared: ‘I have died many times. That’s where I have beaten Christ. Christ died once and resurrected once.’

This is a man who surely will not go gentle into that good night, whatever the cost to his country.